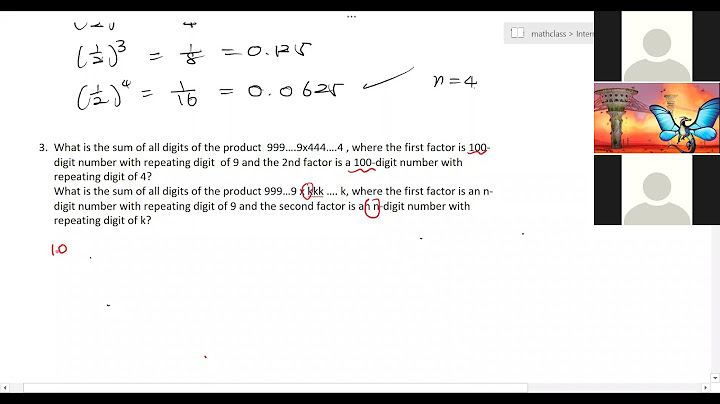

Solution: We know that the diagonals of a parallelogram bisect each other. Also, the median of a triangle divides it into two triangles of equal areas. By the use of these observations, we can get the required result. Let's draw a diagram according to the question statement.  We know that diagonals of parallelograms bisect each other. Therefore, O is the mid-point of diagonal AC and BD. BO is the median in ΔABC. Therefore, BO will divide ΔABC into two triangles of equal areas. ∴ Area (ΔAOB) = Area (ΔBOC) ... (equation 1) Also, In ΔBCD, CO is the median. Therefore, median CO will divide ΔBCD into two equal triangles. Hence, Area (ΔBOC) = Area (ΔCOD) ... (equation 2) Similarly, Area (ΔCOD) = Area (ΔAOD) ... (equation 3) From Equations equation (1), (2) and (3) we obtain Area (ΔAOB) = Area (ΔBOC) = Area (ΔCOD) = Area (ΔAOD) Therefore, we can say that the diagonals of a parallelogram divide it into four triangles of equal area. ☛ Check: NCERT Solutions Class 9 Maths Chapter 9 Video Solution: Show that the diagonals of a parallelogram divide it into four triangles of equal area.Maths NCERT Solutions Class 9 Chapter 9 Exercise 9.3 Question 3 Summary: The diagonals of a parallelogram divide it into four triangles of equal area. ☛ Related Questions: Math worksheets and A parallelogram is a quadrilateral that has both pairs of opposite sides parallel. Parallelograms have many properties that are easy to prove using the properties of parallel lines. You will occasionally use a diagonal to divide a parallelogram into triangles. If you do this carefully, your triangles will be congruent, so you can use CPOCTAC.

A parallelogram is a quadrilateral that has both pairs of opposite sides parallel.

Figure 15.7Parallelogram ABCD with diagonal ¯AC.

This theorem will come in handy when establishing theorems about parallelograms. A common technique involves using a diagonal to divide a parallelogram into two triangles and then applying CPOCTAC. The next two theorems use this technique. Ill prove the first one and let you prove the second.

The last property of a parallelogram that I will mention involves the intersection of the diagonals. It turns out that the diagonals of a parallelogram bisect each other. The proof of this is fairly straightforward, so I'll walk you through the game plan and let you provide the details.

Take a look at parallelogram ABCD in Figure 15.8. It has diagonals ¯AC and ¯BD which intersect at M. We want to show ¯AM ~= ¯MC. The easiest way to do this is to find two triangles that are congruent and use CPOCTAC. The two triangles that we'll try to prove congruent are AMD and CMB. Because opposite sides of a parallelogram are congruent, ¯BC ~= ¯AD. Because vertical angles are congruent, AMD ~= ¯CMB. Finally, we have ¯BC ¯AD cut by a transversal ¯AC, and because BCA and CAD are alternate interior angles, they are congruent. Using the AAS Theorem, we can conclude that AMD ~= CMB. Finish it up by using CPOCTAC.

Figure 15.8Parallelogram ABCD has diagonals ¯AC and ¯BD which intersect at M. Excerpted from The Complete Idiot's Guide to Geometry © 2004 by Denise Szecsei, Ph.D.. All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Used by arrangement with Alpha Books, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. To order this book direct from the publisher, visit the Penguin USA website or call 1-800-253-6476. You can also purchase this book at Amazon.com and Barnes & Noble.

Assumed knowledge

Motivation There are only three important categories of special triangles − isosceles triangles, equilateral triangles and right-angled triangles. In contrast, there are many categories of special quadrilaterals. This module will deal with two of them − parallelograms and rectangles − leaving rhombuses, kites, squares, trapezia and cyclic quadrilaterals to the module, Rhombuses, Kites, and Trapezia. Apart from cyclic quadrilaterals, these special quadrilaterals and their properties have been introduced informally over several years, but without congruence, a rigorous discussion of them was not possible. Each congruence proof uses the diagonals to divide the quadrilateral into triangles, after which we can apply the methods of congruent triangles developed in the module, Congruence. The present treatment has four purposes:

The material in this module is suitable for Year 8 as further applications of congruence and constructions. Because of its systematic development, it provides an excellent introduction to proof, converse statements, and sequences of theorems. Considerable guidance in such ideas is normally required in Year 8, which is consolidated by further discussion in later years. The complementary ideas of a ‘property’ of a figure, and a ‘test’ for a figure, become particularly important in this module. Indeed, clarity about these ideas is one of the many reasons for teaching this material at school. Most of the tests that we meet are converses of properties that have already been proven. For example, the fact that the base angles of an isosceles triangle are equal is a property of isosceles triangles. This property can be re-formulated as an ‘If …, then … ’ statement:

Now the corresponding test for a triangle to be isosceles is clearly the converse statement:

Remember that a statement may be true, but its converse false. It is true that ‘If a number is a multiple of 4, then it is even’, but it is false that ‘If a number is even, then it is a multiple of 4’. Content Quadrilaterals In other modules, we defined a quadrilateral to be a closed plane figure bounded by four intervals, and a convex quadrilateral to be a quadrilateral in which each interior angle is less than 180°. We proved two important theorems about the angles of a quadrilateral:

To prove the first result, we constructed in each case a diagonal that lies completely inside the quadrilateral. This divided the quadrilateral into two triangles, each of whose angle sum is 180°. To prove the second result, we produced one side at each vertex of the convex quadrilateral. The sum of the four straight angles is 720° and the sum of the four interior angles is 360°, so the sum of the four exterior angles is 360°. Parallelograms We begin with parallelograms, because we will be using the results about parallelograms when discussing the other figures. Definition of a parallelogram

The word ‘parallelogram’ comes from Greek Constructing a parallelogram using the definition To construct a parallelogram using the definition, we can use the copy-an-angle construction to form parallel lines. For example, suppose that we are given the intervals AB and AD in the diagram below. We extend AD and AB and copy the angle at A to corresponding angles at B and D to determine C and complete the parallelogram ABCD. (See the module, Construction.) This is not the easiest way to construct a parallelogram. First property of a parallelogram − The opposite angles are equal The three properties of a parallelogram developed below concern first, the interior angles, secondly, the sides, and thirdly the diagonals. The first property is most easily proven using angle-chasing, but it can also be proven using congruence. Theorem

Proof

Second property of a parallelogram − The opposite sides are equal As an example, this proof has been set out in full, with the congruence test fully developed. Most of the remaining proofs however, are presented as exercises, with an abbreviated version given as an answer. Theorem

Proof

Third property of a parallelogram − The diagonals bisect each other Theorem The diagonals of a parallelogram bisect each other.

click for screencast

a Prove that b Hence prove that the diagonals bisect each other.

Notice that, in general, a parallelogram does not have a circumcircle through all four vertices. First test for a parallelogram − The opposite angles are equal Besides the definition itself, there are four useful tests for a parallelogram. Our first test is the converse of our first property, that the opposite angles of a quadrilateral are equal. Theorem If the opposite angles of a quadrilateral are equal, then the quadrilateral is a parallelogram.

click for screencast

EXERCISE 2 Prove this result using the figure below. Second test for a parallelogram − Opposite sides are equal This test is the converse of the property that the opposite sides of a parallelogram are equal. Theorem If the opposite sides of a (convex) quadrilateral are equal, then the quadrilateral is a parallelogram.

click for screencast

EXERCISE 3

Then PQ || Third test for a parallelogram − One pair of opposite sides are equal and parallel This test turns out to be very useful, because it uses only one pair of opposite sides. Theorem If one pair of opposite sides of a quadrilateral are equal and parallel, then the quadrilateral is a parallelogram.

click for screencast

Complete the proof using the figure on the right. This test for a parallelogram gives a quick and easy way to construct a parallelogram using a two-sided ruler. Draw a 6 cm interval on each side of the ruler. Joining up the endpoints gives a parallelogram.

Even a simple vector property like the commutativity of the addition of vectors depends on this construction. The parallelogram ABQP shows, for example, that      Fourth test for a parallelogram − The diagonals bisect each other This test is the converse of the property that the diagonals of a parallelogram bisect Theorem If the diagonals of a quadrilateral bisect each other, then the quadrilateral is a parallelogram:

click for screencast

EXERCISE 5 Complete the proof using the diagram below.

It also allows yet another method of completing an angle

click for screencast

EXERCISE 6

Parallelograms Definition of a parallelogram A parallelogram is a quadrilateral whose opposite sides are parallel. Properties of a parallelogram

Tests for a parallelogram A quadrilateral is a parallelogram if:

Rectangles The word ‘rectangle’ means ‘right angle’, and this is reflected in its definition.

A rectangle is a quadrilateral in which First Property of a rectangle − A rectangle is a parallelogram Each pair of co-interior angles are supplementary, because two right angles add to a straight angle, so the opposite sides of a rectangle are parallel. This means that a rectangle is a parallelogram, so:

Second property of a rectangle − The diagonals are equal The diagonals of a rectangle have another important property − they are equal in length. The proof has been set out in full as an example, because the overlapping congruent triangles can be confusing. Theorem

Proof Let ABCD be a rectangle. We prove that AC = BD. In the triangles ABC and DCB:

so Hence AC = DB (matching sides of congruent triangles).

circle with centre M through all four vertices. We can describe this situation by saying that, ‘The vertices ofa rectangle are concyclic’.

click for screencast

EXERCISE 7 Give an alternative proof of this result using Pythagoras’ theorem. First test for a rectangle − A parallelogram with one right angle If a parallelogram is known to have one right angle, then repeated use of co-interior angles proves that all its angles are right angles. Theorem If one angle of a parallelogram is a right angle, then it is a rectangle. Because of this theorem, the definition of a rectangle is sometimes taken to be ‘a parallelogram with a right angle’. Construction of a rectangle We can construct a rectangle with given side lengths by constructing a parallelogram with a right angle on one corner. First drop a perpendicular from a point P to a line Second test for a rectangle − A quadrilateral with equal diagonals that bisect We have shown above that the diagonals of a rectangle are equal and bisect each other. Conversely, these two properties taken together constitute a test for a quadrilateral to be a rectangle. Theorem A quadrilateral whose diagonals are equal and bisect each other is a rectangle.

click for screencast

a Why is the quadrilateral a parallelogram? b Use congruence to prove that the figure is a rectangle.

click for screencast

Give an alternative proof of the theorem using angle-chasing. As a consequence of this result, the endpoints of any two diameters of a circle form a rectangle, because this quadrilateral has equal diagonals that bisect each other. Thus we can construct a rectangle very simply by drawing any two intersecting lines, then drawing any circle centred at the point of intersection. The quadrilateral formed by joining the four points where the circle cuts the lines is a rectangle because it has equal diagonals that bisect each other.

Rectangles Definition of a rectangle A rectangle is a quadrilateral in which all angles are right angles. Properties of a rectangle

Tests for a rectangle

Links forward The remaining special quadrilaterals to be treated by the congruence and angle-chasing methods of this module are rhombuses, kites, squares and trapezia. The sequence of theorems involved in treating all these special quadrilaterals at once becomes quite complicated, so their discussion will be left until the module Rhombuses, Kites, and Trapezia. Each individual proof, however, is well within Year 8 ability, provided that students have the right experiences. In particular, it would be useful to prove in Year 8 that the diagonals of rhombuses and kites meet at right angles − this result is needed in area formulas, it is useful in applications of Pythagoras’ theorem, and it provides a more systematic explanation of several important constructions. The next step in the development of geometry is a rigorous treatment of similarity. This will allow various results about ratios of lengths to be established, and also make possible the definition of the trigonometric ratios. Similarity is required for the geometry of circles, where another class of special quadrilaterals arises, namely the cyclic quadrilaterals, whose vertices lie on a circle. Special quadrilaterals and their properties are needed to establish the standard formulas for areas and volumes of figures. Later, these results will be important in developing integration. Theorems about special quadrilaterals will be widely used in coordinate geometry. Rectangles are so ubiquitous that they go unnoticed in most applications. One special role worth noting is they are the basis of the coordinates of points in the cartesian plane − to find the coordinates of a point in the plane, we complete the rectangle formed by the point and the two axes. Parallelograms arise when we add vectors by completing the parallelogram − this is the reason why they become so important when complex numbers are represented on the Argand diagram. History and applications Rectangles have been useful for as long as there have been buildings, because vertical pillars and horizontal crossbeams are the most obvious way to construct a building of any size, giving a structure in the shape of a rectangular prism, all of whose faces are rectangles. The diagonals that we constantly use to study rectangles have an analogy in building − a rectangular frame with a diagonal has far more rigidity than a simple rectangular frame, and diagonal struts have always been used by builders to give their building more strength. Parallelograms are not as common in the physical world (except as shadows of rectangular objects). Their major role historically has been in the representation of physical concepts by vectors. For example, when two forces are combined, a parallelogram can be drawn to help compute the size and direction of the combined force. When there are three forces, we complete the parallelepiped, which is the three-dimensional analogue of the parallelogram. REFERENCES A History of Mathematics: An Introduction, 3rd Edition, Victor J. Katz, Addison-Wesley, (2008) History of Mathematics, D. E. Smith, Dover publications New York, (1958) ANSWERS TO EXERCISES EXERCISE 1 a In the triangles ABM and CDM :

b Hence AM = CM and DM = BM (matching sides of congruent triangles) EXERCISE 2

EXERCISE 3

EXERCISE 4

EXERCISE 5

Hence ABCD is a parallelogram, because one pair of opposite sides are equal and parallel. EXERCISE 6 Join AM. With centre M, draw an arc with radius AM that meets AM produced at C . Then ABCD is a parallelogram because its diagonals bisect each other. EXERCISE 7 The square on each diagonal is the sum of the squares on any two adjacent sides. Since opposite sides are equal in length, the squares on both diagonals are the same. EXERCISE 8

Hence ABCD is rectangle, because it is a parallelogram with one right angle. EXERCISE 9

Hence The Improving Mathematics Education in Schools (TIMES) Project 2009-2011 was funded by the Australian Government Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Australian Government Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. © The University of Melbourne on behalf of the International Centre of Excellence for Education in Mathematics (ICE-EM), the education division of the Australian Mathematical Sciences Institute (AMSI), 2010 (except where otherwise indicated). This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.   |

zusammenhängende Posts

Werbung

NEUESTEN NACHRICHTEN

Toplisten

#1

#2

#3

Top 8 zeichnen lernen für kinder online 2022

1 Jahrs vor#4

Top 8 schluss machen trotz liebe text 2022

1 Jahrs vor#5

#6

Top 8 wie fallen calvin klein sneaker aus 2022

1 Jahrs vor#7

Top 5 mi band 3 schrittzähler einstellen 2022

1 Jahrs vor#8

#9

Top 9 sich gegenseitig gut tun englisch 2022

1 Jahrs vor#10

Werbung

Populer

Werbung

Urheberrechte © © 2024 wiewird Inc.